| Call Number | EC-0031 |

| Title | Sagdinan Mar |

| Category | Liturgy of the Hours. |

| Author of Text | Mar Babai the Great |

| Liturgical Context | Night prayers on Sundays in Advent and Christmas seasons |

This is the 18th verse from the hymn, “Brīk hannānā” (“blessed is the merciful one”) from the night prayers (lelya) for Sundays in Advent and Christmas in the East Syriac tradition. The hymn belongs to the category of “Tešbohtā” (“praise”), in praise of the mystery of incarnation. The hymn consists of twenty couplets. Each verse has 4 + 4 = 8 syllables (Sag-dīn-an- mār/ lā-lā-hū-sākh). Because of the theological significance of the text, the breviary prescribes this couplet be sung three times. At some point in the history, definitely before the seventeenth century, the St. Thomas Christians started treating this couplet as a separate hymn. The performance context varied from the beginning of Qurbana on the major feasts of the Lord to the conclusion of festal processions. The usual performance practice is to sing the same text and melody three times in three ascending pitch registers.

The earliest reference to the hymn is in the acrostic hymn in Syriac, written by a Catholic St. Thomas Christian priest, Fr. Chandi Kadavil, popularly known as “Alexander the Indian” (1588- c. 1673). The title of Fr. Kadavil’s acrostic hymn on the Eucharist contains a reference to the opening words of this chant. Fr. Kadavil wrote the acrostic hymn according to meter and melody of “Sagdīnan mār.” It means that the hymn was already popular among the St. Thomas Christians at the dawn of the seventeenth century (i. e., before the Coonan Cross Oath (1653) and the ensuing divisions in the community.

The text is highly Christological and deserves further study. This may very well be the earliest known East Syriac hymn on the subject of hypostatic union and Incarnation. It is, in effect, a paraphrasing of the exuberant acclamation of St. Thomas, the Apostle of India: “Mār walāh,” “My Lord and my God” (Jn 20:28). In those two words, the Apostle acknowledged the humanity and divinity of Christ. In the course of history, the manner of the coexistence of the humanity and divinity in the person of Christ became a topic for heated discussions that shook the foundation of the Christian religion. There is a play on the shades of meaning of the final phrase “lā pūlāga.” It can mean “without doubt,” or “without division.” The alternate translation given above is based on these meanings. The hymn resolves the long-standing Christological controversies (Council of Ephesus and Council of Chalcedon). The special significance the East Syriac Churches in India gave to this hymn is an indication that these Churches were not subject to those controversies. The hymn is a perfect example of the interface of music, poetry, pedagogy, dogma, theology, liturgy, and catechesis. It also represents an era when liturgy was the prime medium for catechesis.

So far, we know of two melodies for this hymn. See one example in Aramaic Project-79. Fr. Thomas Kalayil, CMI sang a different melody during our interview. This video remains to be published. Interestingly, both melodies are different from the traditional melody of Brīk hannānā (see track no. 7 in the CD, “Qambel Maran: Syriac Chants from South India” ). Until further evidence appears, we may presume that these melodies were composed in Kerala.

Joseph J. Palackal

New York

1 June 2018

Given below are excerpts from many email communications I had on this topic with Dr. Zacharias Thundy. These comments could be the starting point for further research on this chant, for example, for a master’s thesis in theology.

Zacharias P. Thundy (October 8, 2017): The hymn was composed during the theological controversies of the time regarding the relationship between the divinity and humanity of Jesus. Without going into details, let me just say that "d’la pulaga" has the meaning of "undivided" referring to the divinity and humanity of Jesus, and not to our act of adoration: "Lord, we worship your undivided humanity and divinity." It all means Jesus is both human and divine. Complex theology it is. So words like "sewiana" and "shuprutha" also have highly technical theological meaning. "Shuprutha" could mean "mia phusis" of Cyril or Council of Chalcedon. I do not know of the theological meaning of "shuprutha" in the Syrian context of the time. Maybe the word means the Chalcedonian "mia phusis" or "Miaphysitism holds that in the person of Jesus Christ, Divine nature and Human nature are united (μία, mia - "one" or "unity") in a compound nature ("physis"), the two being united without separation, without mixture, without confusion, and without alteration." Then there is the theology of the Syrian bishop, Theodore of Mopsuestia: Referring to the two natures in Christ, Theodore writes, “When we try to distinguish the natures, we say that the person of the man is complete and that that of the Godhead is complete (T-120, VIII-8).” Furthermore, he notes that indwelling does not imply a change in nature of either the Logos or the indwelt man (T-121, IX-9), and that Christ’s human will was maintained through the indwelling (T-118, VII-3). Therefore, according to Theodore, Christ is fully human, possessing both human spirit (or rational soul) and human flesh (T-59.22)."

All of this theology has a long tortuous history in the ancient Syriac-speaking world, but it is all reflected darkly in the Syriac hymns. Most of us know little or nothing about it all.

----------

From: Zacharias P Thundy

Date: Mon, Oct 9, 2017 at 11:48 AM

Subject: Re: DLA PULAGA--a theological concept

To: Joseph Palackal

The one who was smarter is the author of the Fourth Gospel who put those words in the mouth of Thomas. That erudite author, well-versed in Indian, Greek, Roman, and Hebrew theologies, was struggling with a fundamental theological problem. He was acutely aware that there is a difference between Dyaus-pita (Father God or Zeus or Jupiter and many gods, whom we call correctly gods or rather as "divine," as in the Greek, Indian, and Roman conceptions of the many gods who share in divinity as in the well-known Upanishadic expression "Aham Brahmasmi." This was the theological problem all the early Christian theologians like the gospel writers had to contend with: How is divinity shared when there is a Supreme Creator God (Pantocrator) as in genesis, the savior gods in all religions, and the continued presence or appearance of saviors in all religions? Was Jesus, the savior, equal to the Father from the moment of conception or did He become divine during his baptism or after his death? The Fourth Gospel says he was "divine" (theos but not ho theos, which is equivalent dyaus pita or Zeus or Jupiter or God the Father) by giving him the Greek concept of LOGOS, implying that it was this WORD that created heaven and earth as in Genesis etc. A difficult theological problem early Christians had to deal with, spawning all kinds of heresies even to this day. Finally, they found the solution in the concept of the Trinity, leaving room for saints (still sharing divinity by being part of the body of Jesus) instead of calling them as gods.

As for a meaningful translation: "We worship you, Lord, as one in your divinity and humanity, "united without separation, without mixture, without confusion, and without alteration." The intended meaning is this because the next four lines explicate this position clearly; Hadu haila; hada marrutha/Had sewiana; hada shuprutha/Lava u lavra;Wal ruh qudsha/Laalam almin; aamen waamen."

-------------------------------

From: Zacharias P Thundy

Date: Mon, Oct 9, 2017 at 3:53 PM

Subject: Re: literal translation

To: Joseph Palackal

Pick your choice:

We adore, my Lord, your inseparable divinity and humanity

My Lord, we adore you in whom divinity and humanity are inseparable.

We adore you, my Lord and my God.

----------------------------------

From: Zacharias P Thundy

Date: Mon, Oct 9, 2017 at 11:48 AM

Subject: Re: DLA PULAGA--a theological concept

To: Joseph Palackal

The one who was smarter is the author of the Fourth Gospel who put those words in the mouth of Thomas. That erudite author, well-versed in Indian, Greek, Roman, and Hebrew theologies, was struggling with a fundamental theological problem. He was acutely aware that there is a difference between Dyaus-pita (Father God or Zeus or Jupiter and many gods, whom we call correctly gods or rather as "divine," as in the Greek, Indian, and Roman conceptions of the many gods who share in divinity as in the well-known Upanishadic expression "Aham Brahmasmi." This was the theological problem all the early Christian theologians like the gospel writers had to contend with: How is divinity shared when there is a Supreme Creator God (Pantocrator) as in genesis, the savior gods in all religions, and the continued presence or appearance of saviors in all religions? Was Jesus, the savior, equal to the Father from the moment of conception or did He become divine during his baptism or after his death? The Fourth Gospel says he was "divine" (theos but not ho theos, which is equivalent dyaus pita or Zeus or Jupiter or God the Father) by giving him the Greek concept of LOGOS, implying that it was this WORD that created heaven and earth as in Genesis etc. A difficult theological problem early Christians had to deal with, spawning all kinds of heresies even to this day. Finally, they found the solution in the concept of the Trinity, leaving room for saints (still sharing divinity by being part of the body of Jesus), instead of calling them as gods.

As for a meaningful translation: "We worship you, Lord, as one in your divinity and humanity, "united without separation, without mixture, without confusion, and without alteration." The intended meaning is this because the next four lines explicate this position clearly; Hadu haila; hada marrutha/Had sewiana; hada shuprutha/Lava u lavra;Wal ruh qudsha/Laalam almin; aamen waamen."

--------------------------------------

From: Zacharias P Thundy

Date: Tue, Oct 10, 2017 at 10:13 AM

Subject: Joe: FYI: You May be Opening an Old Wound in Kerala Church

To: Joseph Palackal

Were we Nestorians or not? The hymn, in my view, is an interesting one only from a historical perspective. As it stands, the Portuguese apparently overlooked it and failed to remove it from our prayers. Or we hid it from their censorship, which is probably the case. We used to sing it loud and clear for centuries "without any hesitation." The words of the hymn can be interpreted as Nestorian. But not necessarily and emphatically.

Why? The hymn also states that there is only one will in Christ "had sewiana." Or is it in the trinity?

Anything wrong with it at all? Yes, from a theological standpoint but not from our "Syrian Christian point of view" from the fourth century. The Latin Church would condemn us Nestorian. Did we care? Yes we did at the Diamper Synod. Do we care now? Yes. We Roman Catholics do not want to be known as Nestorians any more. There is the rub.

I bet the Assyrian Church of the East sings the same hymn with "SAGDINAN." Find out to satisfy your own curiosity. Then draw your own conclusions. Let me know.

Here below see St. Thomas Aquinas:

I answer that, some placed only one will in Christ; but they seem to have had different motives for holding this. For Apollinaris did not hold an intellectual soul in Christ, but maintained that the Word was in place of the soul, or even in place of the intellect. Hence since "the will is in the reason," as the Philosopher says (De Anima iii, 9), it followed that in Christ there was no human will; and thus there was only one will in Him. So, too, Eutyches and all who held one composite nature in Christ were forced to place one will in Him. Nestorius, too, who maintained that the union of God and man was one of affection and will, held only one will in Christ. But later on, Macarius, Patriarch of Antioch, Cyrus of Alexandria, and Sergius of Constantinople and some of their followers, held that there is one will in Christ, although they held that in Christ there are two natures united in a hypostasis; because they believed that Christ's human nature never moved with its own motion, but only inasmuch as it was moved by the Godhead, as is plain from the synodical letter of Pope Agatho [Third Council of Constantinople, Act. 4].

And hence in the sixth Council held at Constantinople [Act. 18] it was decreed that it must be said that there are two wills in Christ, in the following passage: "In accordance with what the Prophets of old taught us concerning Christ, and as He taught us Himself, and the Symbol of the Holy Fathers has handed down to us, we confess two natural wills in Him and two natural operations." And this much it was necessary to say. For it is manifest that the Son of God assumed a perfect human nature, as was shown above (Article 5; III). Now the will pertains to the perfection of human nature, being one of its natural powers, even as the intellect, as was stated in I:79 and I:80. Hence we must say that the Son of God assumed a human will, together with human nature. Now by the assumption of human nature the Son of God suffered no diminution of what pertains to His Divine Nature, to which it belongs to have a will, as was said in the I:19:1. Hence it must be said that there are two wills in Christ, i.e. one human, the other Divine.

Christian Musicological Society of India is immensely grateful to Prof. Zacharias Thundy for sharing his informed insights on the extremely complex topic.

Joseph J. Palackal

New York

16 January 2018

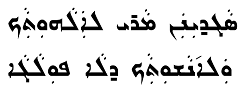

| Syriac Text | |

|

|

| Text Courtesy - Joseph Thekkadath Puthenkudy |

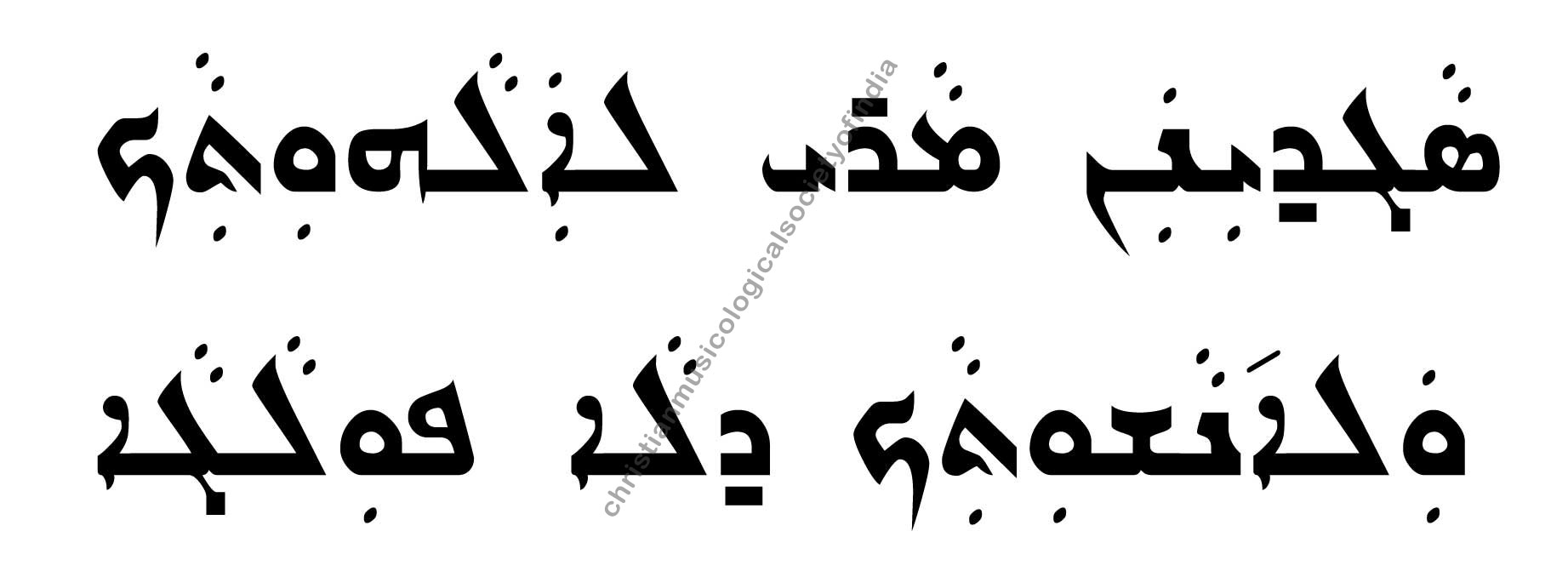

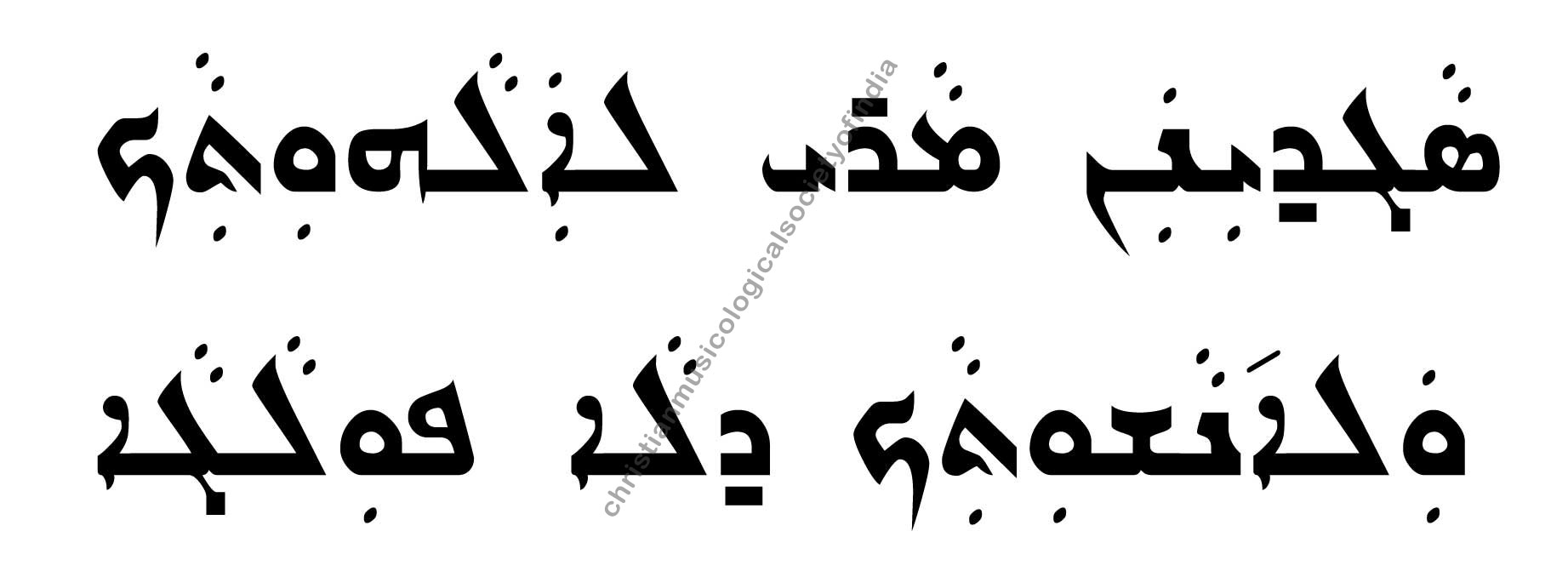

| Syriac Text |

|

| Text Courtesy - Joseph Thekkadath Puthenkudy |

Transliteration & Translation (English)

| Translation | Transliteration | Glossary |

We adore, my Lord, your inseparable divinity and humanity. |

Sagdīnan mār lālāhūsākh Walnāšūākh d’lāpūlāga | Glossary (courtesy: Zacharias Thundyil) Sagdīnan mār (sagdīn + an) = we adore; mār = my Lord; lālāhūsāk (l’ + alāhūsā + akh) = your divinity; walnāšūākh (w’ + al + nāšūsā + akh) = and your humanity; d’lāpūlāga (d’ + lā +pūlāga) = that which [is] without division/ without doubt |

| Translation |

We adore, my Lord, your inseparable divinity and humanity. |

| Transliteration |

| Sagdīnan mār lālāhūsākh Walnāšūākh d’lāpūlāga |

| Glossary |

| Glossary (courtesy: Zacharias Thundyil) Sagdīnan mār (sagdīn + an) = we adore; mār = my Lord; lālāhūsāk (l’ + alāhūsā + akh) = your divinity; walnāšūākh (w’ + al + nāšūsā + akh) = and your humanity; d’lāpūlāga (d’ + lā +pūlāga) = that which [is] without division/ without doubt |

Aramaic Project Recordings:

| S.No | Artist | Youtube Link | Aramaic Project Number | Notes |

| 1. | Dr. Jacob Vellian | Video | AP 79 | |

| 2. | Dr. Joseph J. Palackal teaching Choir members at Birmingham, England | Video | AP 98 | |

| 3. | Bishop Joseph Kallarangatt | Video | AP 91 | |

| 4. | Fr. Sebastian Sankoorikkal | Video | AP 25F | |

| 6. | Fr. Thomas Kalayil, CMI | Video | AP 107E | |

| 7. | St, Jude Syro Malabar Catholic Church, Northern Virginia, USA | Video | AP 101 | |

| 8. | The Prients of Syro Malabar Diocese of Toronto , Canada | Video | AP 134 | |

| 9. | Dr. Thomas Kalayil, CMI | Video | AP 113 | |

| 10. | Fr THOMAS KANJIRATHUMOOTTIL, Athirampuzha | Video | AP 88 | |

| 11. | Fr. Thomas Kalayil, CMI | Video | AP 107E | |

| 12. | Dr. Joseph J. Palackal | Video | AP 109 | |

| 13. | Fr. Augustine Kandathikudilil | Video | AP 117 | |

| 14. | Dr. Joseph J. Palackal with students of Carmel Hill Philosophical College ,Trivandrum | Video | AP 133 | |

| 15. | Dr. Joseph Palackal | Video | AP 143 | |

| 16. | Dr. Joseph Palackal and the Choir team | Video | AP 146 | |

| 17. | Papputty Master (Violin instrumental track) | Video | AP 179 | |

| 19. | Ramsha Mariam Payyappilly | Video | AP 196 | |

| 20. | Children Group | Video | AP 243 |

Christian Musicological Society of India. Do not use any part of this article without prior written permission from the Christian Musicological Society of India. For permission please send request to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.